Fastidious Themes: Three Great Instrumental Albums for Studying

By Euan MacDonald

Thumbnail & Banner Photo by PolyGram Filmed Entertainment

Many, unknowingly, may have criteria for the music they’ll allow while studying. Some switch anything on (as long as it’s loud), and others prefer certain genres (death metal may ease certain pains). To me, the genre or volume is immaterial: My only opinion is on lyrics. I prefer my moments of studious clarity to be accompanied by music that lacks constant verbiage. Writing and listening are arts both deserving of equal reverence, justifying a divide: To pay attention and give credit to one, you could be forced to neglect the other. I find I can circumvent this with a few important touchstones: No or little lyrics (Mozart has a good track record), long or transitioning tracks, and lengthy albums. All three projects recommended here - covering a zenith of ambient work in the nineties, a celebration of mash-up culture in hip-hop instrumentals, and one of many classics from the greatest of the greats - hold at least two of the aforementioned qualities. All are also endorsed for: Waking up, falling asleep, dreaming, daydreaming, staring at the sky, walks on the beach, rainy days, baking, painting, and any assortment of beautiful or serene moments.

Selected Ambient Works Volume II by Aphex Twin

Do you hear when you dream? Answers may differ. When I remember my unconscious moments - which evaporate within the first waking hour - they play back to me like a film with its sound removed; I can remember dialogue and moments that demand certain audible reactions, but I lack the actual memory of the sound itself. I must foley the sounds in, recreate the words of whoever invaded my subconscious with my internal voice. One must imagine the two-and-a-half-hour album (recently expanded to three) was crafted from similar experiences. Aphex Twin (real name Richard D. James) has said that he slept only two hours a night while making Selected Ambient Works Volume II (constantly abbreviated to SAW II), would lucid dream, and much of the LP came of him recreating the sounds he heard upon waking. The result, celebrating its thirtieth anniversary this year, is a meditative and spiritual experience of impressive minimalism. The album itself lacks words - save for sparse moments, like on track #12 (White Blur 1) when a police interview with a woman who murdered her husband is sampled - and coinciding with its absent lyrics is an absence of conventional instrumentation, songs dominated by eerie synth leads. The eponymous ambient nature of the album makes it hard to pin down, hard to describe, and even harder to surpass - Its indelible mark on music reverberates thirty years on. A description is made even more difficult by the fact that the tracks lack names and are only known by numbers in descending order down the tracklist: The first song is “#1”, the tenth song is “#10”, and so on. However, unofficial names were popularized amongst fans due to artwork that was attached to tracks on physical releases (both numerical and visual titles will be stated here - and all will be according to the numbers provided in the expanded edition). Why does this album built on the back of sleep deprivation and rapid eye movement provide study comfort? While unconventional, and some tracks - like the aforementioned White Blur 1 - become dark and almost disturbed at times, the nature of the album can provide serenity like no other with its industrial hum - such as Rhubarb (#3), a favourite for the realm its enigmatic synths inhabit; the dream Richard had for this one must’ve had a pleasant ending. Another popular track, only put on streaming with the recent re-release, is Stone In Focus (#19): A ten-minute oasis, perfect for reading long chapters and late-night essay revision. In this vein, soft and lullaby-esque tracks are spread throughout Aphex’s eclectic IDM catalogue: aisatsana [102], Avril 14th, and Nanou 2 being a few out of the many. Other tracks on SAW II hold similar magic - Lichen (#21) and Cliffs (#1) - but the quiet fun of such an environmental odyssey of a project is just pressing play while you cram for multiple hours, lost in the images Richard may have seen once upon a sleep: Windowsills, weathered stones, trees and tassels (all speculated track titles). For similar experiences check out Boards of Canada’s In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country, Aphex’s earlier Selected Ambient Works 85-92, and Brian Eno’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports.

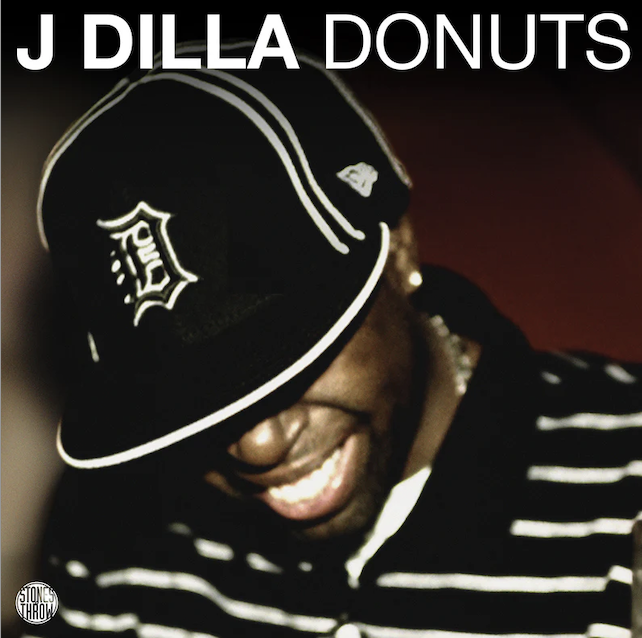

Donuts by J Dilla

What could you make sitting in bed? James Yancey - known professionally by his alias of J Dilla or Jay Dee - answered in February of 2006 with his instrumental hip-hop album Donuts, made almost entirely from his hospital bed. Stories of the production of Dilla’s final album, released on his birthday three days before he succumbed to a combination of rare blood diseases at the age of 32, vary wildly (He’d be 50 this year - happy birthday, Dilla). One from his mother describes how Dilla’s hands would swell, and she would have to massage them as he continued to produce solely on a Boss SP-303 sampler and portable turntable. As an album flowering from such unfair suffering, it seems almost spiteful how beautiful the songs are: Most tracks run under two minutes, with Donuts being a strange compilation of vibrancy and soul. It features no lyrics save for short gasps, shouts, and sentences surgically extracted from living and dead artists alike, musicians of past genres and generations: Specimens uprooted from music history include R&B cornerstone Dionne Warwick on Stop!, progressive rock innovator Frank Zappa on Mash, and on Don’t Cry, a song dedicated to Dilla’s mother, The Escorts provide a soulful backbone. The real interest for studious people in this beautiful goodbye, though, is its seamless track-to-track transitions, compliments from a project unblemished by words. In the hands of the producer only, beats are allowed to flow seamlessly into other beats. J Dilla commits himself to this fully, ending the album with an infinite loop. Each dense yet brief track disappears into the following song without notice from the listener, floating uninterrupted, a forty-three-minute ballad. Perhaps the most noticeable moment in music when committing oneself to another task is the gap between the medley - expect nothing but unadulterated sound from Donuts. Similar albums include DJ Shadow’s Entroducing…, The Avalanche’s Since I Left You, and Nujabe’s Metaphorical Music.

‘Round About Midnight by Miles Davis

The sphere of jazz is full of large personalities in the forms of the contemptuous Mingus, an irate Jones, and a tragic figure in Chambers. However, Miles Davis somehow trumps all: An eccentric maverick, he is now and forever at the forefront of most jazz forms due to his constant innovation within the genre. Kind of Blue remains the best-selling jazz album of all time by RIAA standards and a staple within popular music culture. My choice, however, as both a greeting to a new day, a late-night end, or a session of cramming, remains his 1957 studio album ‘Round About Midnight. Its first feature that grants it deserved recognition amongst Miles’ other flawless works such as the avant-garde orchestrations on In a Silent Way and the modal methods on Milestones is its ensemble cast in the form of The Miles Davis Quintet, a jazz band formed and restructured under many different lineups, assembling with the likes of pianist Red Garland, double bass player Paul Chambers, drummer “Philly” Joe Jones, and legendary tenor sax player John Coltrane for Midnight’s effervescent tracklist. Although not sitting atop the rankings for Davis’ best album by any means, it is effective as both a musical means to laser-hone your focus on any work you deem worthy, and to achieve a peaceful mood that may alleviate stress of many colours. ‘Round Midnight (originally the product of Thelonious Monk, a piece now a jazz standard) opens delightfully slow and revels in its pace - the masters are in no hurry. Bye Bye Blackbird lives firmly in the album’s center, singing like the titular warbler: Davis breathes animal life into the recording, but these are lazy fowl - it is another song that makes no unneeded efforts. Only six compositions make up this NYC-recorded work, products of three sessions between the quintet. It finishes at thirty-nine minutes, but is instantly replayable: Speaking volumes, yet there are no words to get tired of. Similar albums include the aforementioned Kind of Blue, Chet Baker’s Chet Baker Sings, and the self-titled collaboration of the duo Duke Ellington & John Coltrane.

In closing, our relationship with repetition can be both endearing and aggravating. We rewatch beloved films, continuously loop our favorite songs, and reread the most personally impactful books. When you think of something that’s changed you in the past, you can feel it in your heart sometimes that re-experiencing it may change you again. But when we get to know something well enough, we can also begin to hate it: And three albums may not be enough for one’s studying milieu, the environment that envelops them as they work and toil away. Change could be needed. So if these recommendations don’t suit you or don’t satisfy in simply not amassing enough music in the sense of minutes and seconds, you can use their criteria or the footnoted honorable mentions or other sisters in the genre through these picks to expand and grow, as we all do in our appreciations and tastes within art. This advocacy comes from my own heart: My list will be different in a week, too.