Sorry For Your Loss, World

Written by Rita Jabbour

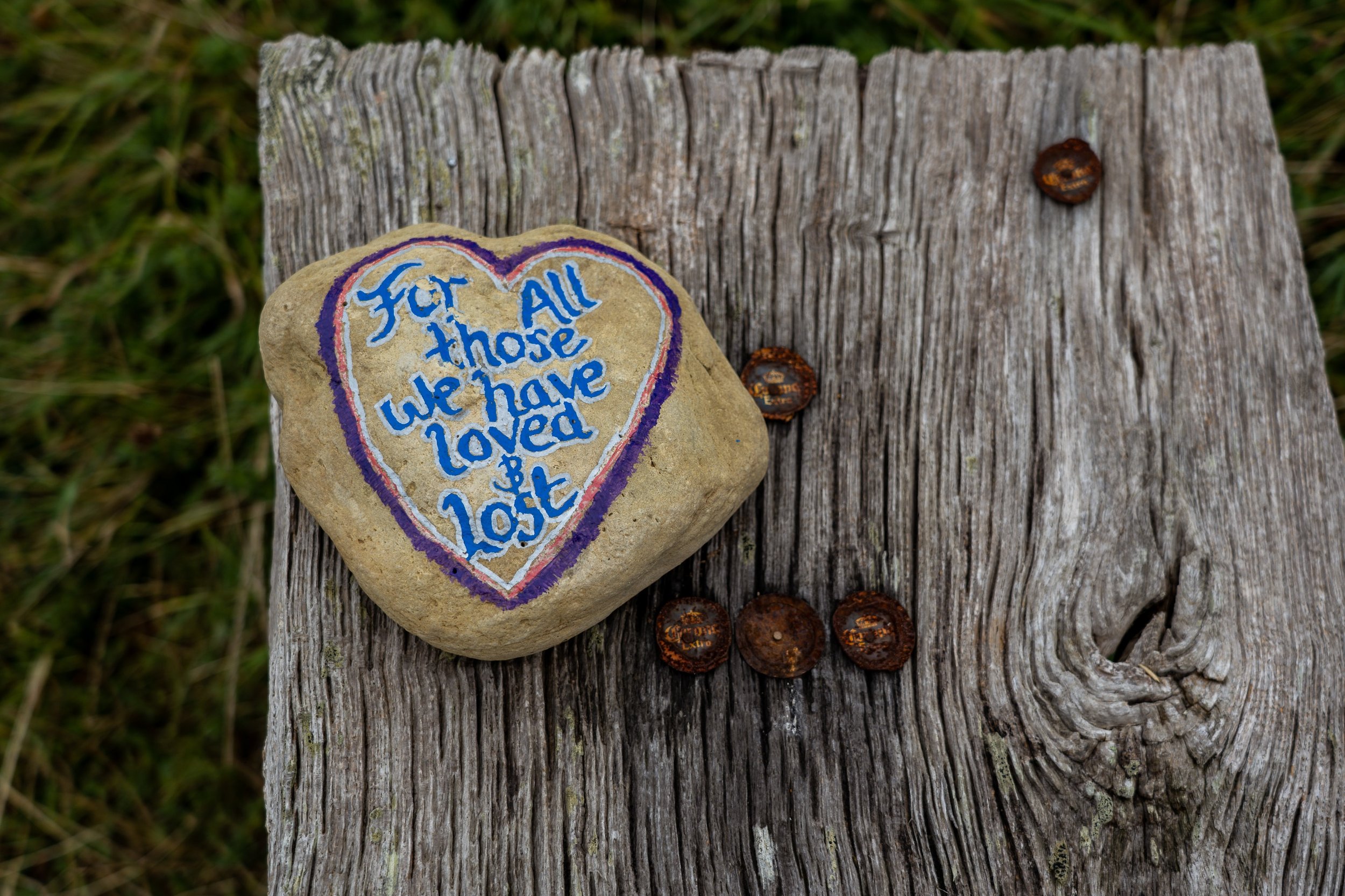

Thumbnail Photo by K. Mitch Hodge on Unsplash

Every once in a while, the universe graces us with a world-changing crisis, whether that may be a world war, pandemic, or natural disaster. We are no strangers to catastrophes because we live in an era where we can ask our grandparents about World War II, hear about the emergence of global warming from our parents, and share stories about the pandemic. Every generation experiences its own events, which unravel the reality of the world: it is not as safe or fair as we were brought up to think it is. While youthhood is typically considered a time of exploration and curiosity, the COVID-19 pandemic quickly stripped that opportunity away. Instead, Gen Z has had to learn to cope with all the stressors of growing up, as well as the anxiety of a global pandemic. We have had to navigate our way around a baffled world while holding ourselves together as we enter our formative years. Grief is the natural response to a significant loss. Although it typically refers to the death of a loved one, it also applies to the loss of meaningful aspects of life. And that is precisely what was lost during the pandemic.

Photo by Edwin Hooper on Unsplash

Not only did we lose the daily life to which we were accustomed, but we lost relatives, friends, and colleagues. We heard about our friends’ family members dying from the virus and their friends’ relatives passing away. If that does not sound traumatic and grief-inducing, then I don’t know what does. We experienced the world as we know it change; everything from school and work to grocery shopping and leisure activities were functioning differently. As young adults growing up during this time, we missed out on chances to see concerts, festivals, and carnivals. We lost opportunities to have beach days, picnics, and game nights. Quarantining meant skipping out on tons of parties, gatherings, and road trips. All the activities that define what it truly means to be a teenager or young adult were unmentionable and impossible to pursue. We were left to grow up in a state of the world in which we weren’t permitted to do so in the way we would have wanted. Nothing was the same. We felt both micro and macro loss. In an instant, the world lost any sense of normalcy and safety and was launched into a spiral of chaotic energy with which no one knew how to deal. To make matters worse, human connection, the supposed holy grail of support, was inaccessible, leaving millions stranded in their homes without the bare minimum of social contact. Suddenly, every individual on earth who was affected by the pandemic was surrounded by a collective cloud of grief.

Although we can safely say that we are no longer in the eye of the storm, we can’t forget that the virus is still affecting many individuals and their families as it did during the pandemic. It is still important to acknowledge all we lost and the grief we undoubtedly felt. It may be that many of us were unable to define our emotions amid the pandemic; there is nothing quite as frustrating as not knowing what one is feeling. The Swiss-American psychiatrist, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, established the well-known theory of grief in which she lists five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Years later, in his book “Finding Meaning: The Sixth Stage of Grief,” author David Kessler proposes a sixth stage of grief: meaning. Since we are well past the “how to deal with your pandemic grief” phase, I believe looking for some light at the end of the tunnel is our best choice moving forward.

There are several things I hope we have learned from the pandemic. The first is recognising how fleeting and fragile life is. We witnessed healthy individuals get terminally sick and pass away, families fall apart, and lives upend. I am personally not fond of the saying “look on the bright side” because I would very much prefer it if those people were still alive over learning a lesson from their death. However, the past cannot be altered, and I can’t deny that life’s fragility has been revealed. I hope we can keep that in mind in the future, never taking a moment for granted. And if not, at the very least I hope we can recall the lost and live a few moments of our day on their behalf, basking in the sunshine they’ll never feel on their face, admiring nature’s sounds they’ll never hear, and appreciating the company of those they’ll never have the blessing of meeting again.

Photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash

Secondly, the immense loss we observed has hopefully taught us all to be a little more sensitive and caring towards others. That means both to people who are nearing the end of their lives and those who are losing or have lost a loved one. If collective grief has taught us anything, it is that grieving is not a pleasurable experience. With that said, we should be trying everything in our power to comfort those who ultimately have to encounter it. Be there for those who have suffered a loss as long as you are able to. It’s important to remember that grief perseveres; comfort grievers not only immediately after their loss but continuously. It will only get worse for them and having you around through the toughest times of their mourning journey will mean the world to them. Remind them that they are loved and cared for, and that their pain is shared and valid. And to those nearing the end of their lives, express your affection and gratitude for them. Talk about the reality of death not as though it were an enigma but honestly and directly. It is the secrecy which causes the most fear of dying. There is nothing more tragic than dying with trepidation. Give your loved one a final parting gift that will ease their apprehension.

Thirdly, I pray that the world has grown a little more sensitised to the importance of discussing loss and grief. As mentioned, in one way or another, everyone affected by the pandemic experienced grief, whether through losing someone they love or losing the life they had. Thus, it is no secret that the world was grieving for an extended period. Recognising this loss is necessary in order to move on, and talking about it is even more essential. Canadian youth’s mental health quality has declined throughout the pandemic, and grief likely plays a prominent role in the latter. So, normalise talking about your feelings, mental health, and, most importantly, any post-pandemic residual grief that pops up in your mind.

Ultimately, a lot has changed since the COVID-19 pandemic. People we love and care about have been lost. Time stood still during quarantine, leaving us with limited activities we could pursue: we lost time and we lost a state of being. It is never too late to address one’s grief; think back to the last two to three years and consider what you’ve lost. Talk about them with a friend or family member because grief does not just go away. It becomes a part of who you are and becomes moulded into the version of yourself that you grow into. To quote Marvel’s Wanda Maximoff: “It's just like this wave washing over me again and again. It knocks me down, and when I try to stand up, it just comes for me again.” To those who are still grieving the loss of a loved one, I’m sorry. To those who are still grieving the loss of life as they knew it, I’m sorry. This has been a heavy and collective grief that has spread across the globe— a type of grief which has not been experienced since the last world catastrophe. With that, I must say sorry for your loss, world.