The Whimsical World of Wes Anderson

Written by: Amani Rizwan

Banner and Cover Photo by Amani Rizwan

One of the oldest pieces of advice in art is: “Show, don’t tell.” Most filmmakers do just that—suggest, imply, and reveal in shades. Then there’s Wes Anderson, who doesn’t just show you his world; he grabs you by the collar and flings you into it. In his world, rooms are pastel-perfect, families are catastrophically flawed, and every frame is obsessively symmetrical, like a dollhouse assembled by someone with a deep fondness for visual order and emotional chaos. One glance, one whip pan, and you know: you’re in Anderson territory.

His signature aesthetic doesn’t just sit on the screen—it shouts for attention. With sets that look like dioramas and a level of visual exactitude that borders on architectural, his films feel less like they were shot on location and more like they were hand-built by a watchmaker. Each shot is planimetrically perfect, meaning the camera sits perpendicular to the action, giving you a dead-on, symmetrical view. It’s a technique that makes his worlds feel artificial yet somehow comforting, like flipping through a perfectly preserved scrapbook.

Colour is another tool in Anderson’s accomplished arsenal. He has a distinct philosophy: each shade speaks a language. Red, often a marker of grief, swirls through “The Royal Tenenbaums,” a film thick with unresolved family wounds. His palette is as deliberate as his camerawork, conveying emotion without needing a word of dialogue—a gift he might have inherited from one of his inspirations, French New Wave director Éric Rohmer, who mastered the art of colour-infused mood.

Image by Fox Searchlight Pictures

One of Wes Anderson’s greatest strengths lies in his ability to weave complex, deeply human themes into his meticulously crafted worlds. At the heart of most Anderson films is a broken family, barely holding on but still trying. From “The Royal Tenenbaums” to “The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou,” to “Fantastic Mr Fox”, his films dig into the messy, tangled webs of parenthood, sibling rivalry, and the scars of unresolved love. His families are bizarre and dysfunctional, yet you can’t help but root for them, a testament to Anderson’s knack for tapping into universal, often painful, themes.

Image by Touchstone Pictures

But Anderson doesn’t stop at the typical nuclear family—he explores surrogate families too. “The Darjeeling Limited” follows estranged brothers reconnecting on a train through India (a personal favourite); in “Moonrise Kingdom,” two runaway kids create their own version of family among a troop of scouts and misfit friends. This recurring search for belonging echoes in each of Anderson’s misfit characters, who long for acceptance, only to find that home isn’t necessarily where or who you started out life with —it’s where and those you end up with.

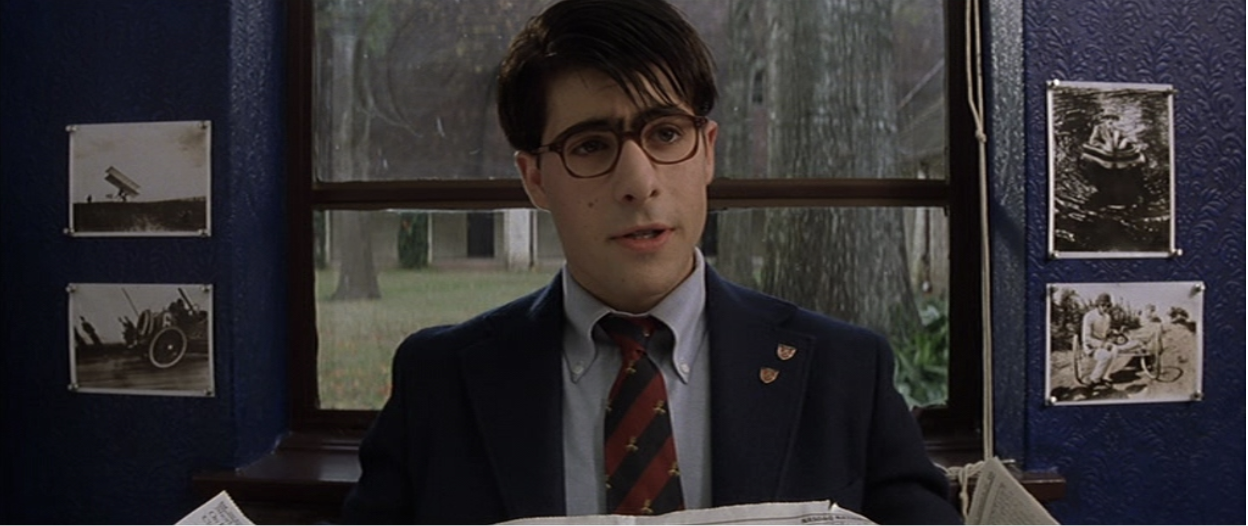

Beyond family dynamics, Anderson’s films frequently explore the complexities of identity and the often awkward journey of self-discovery. His characters are driven by a desire to define themselves, wrestling with past mistakes, societal expectations, or inner insecurities. Take “The Grand Budapest Hotel”, where the fastidious concierge, M. Gustave, creates his own identity through charm and devotion to his hotel’s reputation, a self-crafted persona as vivid as the hotel’s decor. Similarly, in “Rushmore”, Max Fischer throws himself into an array of eccentric extracurriculars, each new activity a part of his relentless pursuit of significance, even as his self-worth wavers beneath the surface. Anderson’s protagonists are often dreamers, misfits in meticulously crafted worlds, searching for a sense of purpose or authenticity. This quest for self—frustrating, sometimes absurd, yet deeply human—resonates through each film, emphasising that personal growth is not a linear path but a series of weird, often bittersweet detours.

Image by Fox Searchlight Pictures

Then there are Anderson’s unforgettable characters, who, each with their own peculiar cocktail of ambition and trauma, are striking. They’re driven by deep, often absurd desires—a need for adventure, revenge, love, or redemption. They’re “character-first” creations, and they’ll stop at nothing, even if their plans go up in smoke (which they often do, comically). Think of Max Fischer in “Rushmore,” whose quest to win the affection of a teacher is as misguided as it is heartbreaking. Or take Mr. Fox and his gang of wild animals in “Fantastic Mr. Fox”, a mismatched crew with a grandiose, absurd mission to outwit three ruthless farmers. Despite their animal instincts, they grapple with very human insecurities and ambitions—Mr. Fox himself is a perfectionist facing a midlife crisis, itching for adventure while trying to be a responsible father and husband.

Image by Touchstone Pictures

Anderson’s distinctive music choices add another layer to his world. Music in a Wes Anderson film isn’t merely a backdrop—it’s a guide, shaping how audiences navigate the emotional and narrative landscape. The tracks he selects often reflect the inner lives of his characters or underscore the thematic undercurrents of the story. He pulls from a rich, eclectic playlist that spans British Invasion rock, folk classics, and even Brazilian bossa nova covers (listen to Seu Jorge’s renditions of Bowie classics in “The Life Aquatic” if you want the full effect). With longtime music supervisor Randall Poster, Wes Anderson has consistently handpicked tracks from legends like The Kinks, David Bowie, The Rolling Stones, and Devo. Devo’s frontman, Mark Mothersbaugh, even composed the scores for Anderson’s first four films, from “Bottle Rocket” (1996) to “The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou”. Yet, it’s perhaps, in my opinion, the haunting scene in “The Royal Tenenbaums”, set to Elliott Smith’s “Needle in the Hay,” that best captures Anderson’s talent for soundtracking. In this moment, Richie Tenenbaum (Luke Wilson) quietly cuts off his hair before attempting suicide; the steady, sombre chords of Smith’s song align perfectly with the character’s actions, with each shaky note echoing Richie’s fragile emotional state. Each track in Anderson’s work is meticulously chosen, more like a character than a complement, often bringing out a side of the film that would otherwise go unnoticed.

In a sea of gritty realism and digital effects, Anderson’s work feels almost rebellious, a handmade artifact in a factory-made industry. His films are poignant but absurd, whimsical but deeply resonant, a fusion of fine art and raw human experience. They remind us that life’s struggles—be it family woes, romantic misadventures, or personal failures—are often both tragic and comedic, a bittersweet balancing act.

If anything, Wes Anderson has proven that you don’t need to reinvent the wheel to create art; you just need to colour it, frame it, and push it a little to the left, and right into place.